In the 2006 series “Bill Moyers on Faith and Reason,” Mr. Moyers discusses the power of mythology for community and connection. Myths, he argues, have historically worked not only to educate people but to connect whole societies together by affirming the values and ideologies central to the community. Myths play a critical role as symbolic storehouses for the ideals and principles that form the heart of a society and identity of its members.

Author: mike chupa

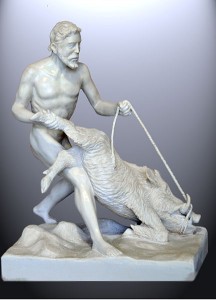

The Trials of Heracles

Heracles (Hercules, in Latin) is considered by many to be the greatest of all Greek mythological heroes. The son of Zeus and a mortal woman, he is hated by the goddess Herra, the wife of Zeus. Her attempt to kill him as an infant is thwarted when he strangles the poisonous snakes she places in his crib. By use of a potion, she later tricks Heracles into killing his wife and children; when the effects of the poison wear off, he is struck by grief, and agrees to undertake twelve impossible trials given him by the jealous Herra to earn redemption.

Heracles, however, undertakes all of the seemingly impossible tasks, conquering them one by one, battling fierce lions and serpents, moving earth and rivers, and then descending into and returning from Hades for his final trial. Upon completion, he walks into a burning pyre and is reborn into eternal life as a god.

The finale represents the death of the Ego, and our rebirth as a hero who lives in service of the divine – the Soul.

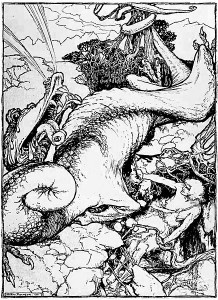

Siegfried and the Dragon

One of the greatest heroes in Norse mythology is Siegfried, and perhaps the greatest telling of his story is in Richard Wagner’s “The Ring of the Nibelung” opera.

Siegfried is the grandson of Wotan, the King of the Gods, who had decreed that only a hero of pure heart, who knew no fear, could forge a sword strong enough to defeat the vicious and terrifying dragon, Fafnir, who protected a vast treasure of gold – and the Ring of Power.

Mime, a Nibelung dwarf, coveted the Ring and, having raised Siegfried after his mother had died in childbirth, intended to kill him. Siegfried, however, bravely fought the dragon and, upon killing him, tasted his blood, an act which gave him the ability to understand the language of nature (specifically of the birds); he absorbed nature into his system. The birds told him of Mime’s treachery, whereupon he killed the dwarf.

The defeat of the Dragon Fafnir represents the acquisition of the skills necessary to find and reconnect with our souls. In Jungian psychology, the Dragon represents the Ego; when you conquer the Ego, you bring it into service of the Soul.

The Lament of Icarus

In Greek Mythology, Icarus was the son of Daedalus, a master craftsman who was imprisoned on the Isle of Crete by King Minos. Daedalus fashioned wings for them to escape, but, according to the poet Ovid, he issued the following warning to his son:

“Let me warn you, Icarus, to take the middle way, in case the moisture weighs down your wings, if you fly too low, or if you go too high, the sun scorches them. Travel between the extremes.”

Out of youthful impetuousness, Icarus defies his father, flies too close to the sun which melts his wings of wax, causing him to plunge to his death in the sea below. Youthful exuberance and energy must be balanced and tempered.

Childhood & Adolescence

Coming from the infinite of the Divine Feminine, or the Implicate Order, children have no concept of the forms, parameters or limits of this physical world.

It is incumbent upon the elders of society to steward youth from unlimited narcissism to a balanced and measured life. They must help contain the powerful feelings, emotions and energy of youth until they are ready to handle them.

This necessity beautifully illustrates the complete, golden ring that makes up our lives, from infancy to the last days of old age. We begin with a consciousness that is perfectly aligned with nature (hence, the innocence and naivete of childhood, moving to the recklessness and passion of adolescence), we move into the conflicted nature of adulthood, often characterized by Hamlet (should I take action? should I avoid it? who am I?), and, ideally, we move into a conscious realignment of our ego lives with our souls.

At every stage of this process, youth serves the aged, the elderly serve the young – we have incredible opportunities at every stage of life and consciousness to be generative, compassionate and loving!

Why Take the Journey?

You take the Journey because you have no other choice! As the poet Machado so eloquently states, there is no road – you create your road with every step you take. When you hear the Calling from your soul, you with either answer it or you won’t – but either way you will embark upon a journey!

Life is a spiritual journey, a soulful journey of finding meaning and awareness, of bringing your everyday life into balance with your deepest self, your soul. Mythologist Joseph Campbell noted in his study of global mythologies that every culture has a hero myth that follows, more or less, the same pattern:

• The Calling

• The Quest / Journey

• The Fall

• The Return

The hero myth is really a metaphor for our own spiritual journey, from alienation to redemption.

We all take this journey – it is the nature of our existence. The question is, Who’s Journey are You Taking? Are you living the life you were born to live? Or are you living the life your parents, your church, your school, or your culture has demanded of you?

The Journey is about waking up and living your very own life, the life only you can live. The universe and humanity are depending on you!

The Divine Feminine

We come into this world through the feminine, the Mother Earth, represented throughout the history of human mythology. For much of human prehistory, the guiding myth for humanity was centered in the notion of the Great Mother, from whom all life flowed, through which all life was interwoven and connected. We come from oneness, from love, the Mother Goddess representing the sacred and indivisible wholeness to which we ultimately must return.

The feminine energy, however, has been repressed in our culture, but is an indispensable aspect of human consciousness. It must be brought back into consciousness and restored to full balance with the masculine if we are to achieve a harmonious balance between these two essential ways of experiencing life.

As the wonderful author Anne Baring notes in her work, The Divine Feminine:

This is why the image of the Divine Feminine is returning to us now, to help us recover not only our sense of trust in life but also the relationship with a dimension of consciousness that we have, in our drive to be in control of life, ignored.”

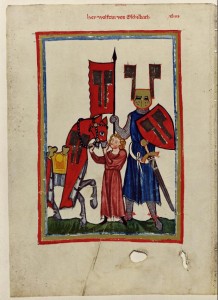

The Story of Parsifal and the Grail Myth

The story of Parsifal is part of the medieval legend of King Arthur and the Quest for the Holy Grail. The Grail myth dates back to at least the twelfth century in Europe, and was transmitted in various versions, including French (from the poet Chretien de Troyes), English (Le Morte Darther, by Thomas Malory), German (Wolfram von Eschenbach’s version, which became the basis for Richard Wagner’s “Parsifal” opera) and others. The Grail myth speaks directly to our psyche, and in particular, as the great Jungian analyst Robert A. Johnson notes in his seminal work, “He,” to the development of the psychology of the masculine, in both men and women – and it is as relevant now as it has ever been.

The myth surrounds the wounded Fisher King, Amfortas, the king of the Grail castle. He is in agonizing pain, and the kingdom suffers as a result. The Fisher King wound, in psychological terms, is a common condition for Western Man, where every young man, as Johnson notes, “has naively blundered into something that is too big for him. He proceeds halfway through his masculine development and then drops it as being too hot. Often a certain bitterness arises, because, like the Fisher King, he can neither live with the new consciousness he has touched nor can he entirely drop it.” This wound, however, is crucial for the development of consciousness, for its redemption, through the intercession of Parsifal, is what leads to the complete integration of the Self – it is what leads to a life of self awareness, contentment, passion and authenticity.

The court jester explains that the Fisher King could only be healed through the actions of an innocent fool, who would spontaneously need to ask a specific question. As Johnson again so eloquently explains, “A man must consent to look to a foolish, innocent, adolescent part of himself for his cure. The inner fool is the only one who can touch his Fisher King wound.”

Parsifal’s Story

Enter Parsifal, a name which means “pure fool,” an innocent young man raised by his overly-protective mother in poverty, knowing nothing of his dead father (who himself was a knight), without any direction or schooling. He is dazzled one day by the appearance of a group of knights who visit his village and, to his mother’s dismay, decides with all the bluster of youth to seek them out to become a knight himself. She agrees to let him go, but gives him a homespun garment that he elects to wear for much of his life; this garment, Johnson notes, represents the “Mother Complex” in psychology, and will prove costly to Parsifal in his development.

Parsifal finds and enters Arthur’s Court but is initially ridiculed and expelled; however, legend held that a damsel in Arthur’s Court who had not smiled for years would burst into laughter at the sight of the greatest knight – which she did at the sight of innocent Parsifal. The Court immediately held Parisfal in high regard and Arthur knighted him on the spot.

Parsifal, naive and not burdened with fear or anxiety, seeks out the most fearsome knight of all, the Red Knight, a warrior so fierce he had never been defeated. Parsifal, in his earnest naivete, confronts him and asks him for his horse and armor. Laughing, he agrees, but only if Parsifal can take it. Predictably, Parsifal is knocked to the ground by the powerful knight but, as he fell, Parsifal throws his dagger into the Red Knight’s eye, killing him. This victory, as Robert Johnson surmises, represents the integration of the “shadow side of masculinity, the negative, potentially destructive power . . . [he] must not repress his aggressiveness since he needs the masculine power of his Red Knight shadow to make his way through the mature world.”

The newly empowered knight goes out seeking battle and adventure, rescuing maidens and defeating opponents, but not killing them; any knight Parsifal overcame he instead instructed to join Arthur’s Court and swear allegiance to him.

The First Encounter with the Fisher King

One day along his heroic quest, Parsifal sought lodging, but was told there was no place to stay for miles. He then encountered a man fishing in a boat on a lake, and asks if he knows of any place to stay for the night. The fisherman, the Fisher King, tells him to go down the road a little bit and go the left. Parsifal obliges and suddenly finds himself on the grounds of the Grail Castle, windows gleaming, knights and ladies greeting him, the splendor of which he had never dreamed of in his life.

A great ceremony was about to begin, one which occurred every evening. A great feast and celebration was held where maidens brought out to all assembled the Holy Grail, from which all would partake, immediately granting them whatever they desired – everyone, that is, except for the Fisher King. Because of his agonizing wound, he was unable to drink from the Grail, and his affliction continued to wreak havoc across the kingdom.

During his quest, Parsifal had encountered a mentor, Gournamond, who had instructed him in the ways of knighthood. When encountering the Holy Grail, Gournamond instructed Parsifal to ask an important question, “Whom does the Grail serve?” This was the question that would heal the Grail King’s wound. However, his mother had also told him not to ask too many questions and hers was the advice Parsifal heeded this time in the Great Hall. All assembled knew the prophecy that one day an innocent fool would enter the castle and ask the question that would heal the King – all except Parsifal – and very quickly the ceremony ends, with everyone retiring for the night. The next morning, Parsifal rides out and the Grail Castle disappears.

The Wasteland

This loss tormented Parsifal, and it would take years of grueling, rigorous battles and quests before Parsifal realized that the homespun garment that he wore beneath his armor – the psychological symbol of the Mother Complex – had to be removed before he could partake of the Grail and heal the Fisher King.

Parsifal spends some twenty years earning his way back to the Grail Castle. They are difficult years, however, and he grows in bitterness and disillusionment; these represent the difficult years of middle age, where one begins to question one’s very existence and the choices made. After twenty years of searching in vain for what was lost in his first encounter at the Grail Castle, Parsifal has had his arrogance and pride beaten and humbled. One day, along his latest quest, he is introduced to a forest hermit.

At first, the hermit scolds him for his failures – especially for not asking the question when he first encountered the Fisher King. However, he soon softens, sympathizing with Parsifal, and then invites him to go down the road a little bit and go to the left . . .

Returning to the Grail Castle

Again, Parsifal suddenly finds himself on the grounds of the Grail Castle, this time, however, with twenty long years of earned experience and humility. Again, he finds himself in the midst of the great feast and celebration where maidens brought out the Holy Grail for all to partake.

This time, however, Parsifal asks the question, “Whom does the Grail serve?” The simple act of asking the question immediately heals the Grail King and the entire Castle erupts in celebration! What is the answer to the question? “You, My Lord, the Grail King.” And what exactly does this answer mean? Very simply, we serve something far greater than ourselves. Carl Jung, the great psychologist, would say that by asking this question, one comes to the realization that the Ego now comes into service of the Self.

The goal of life is not merely to attain personal happiness. Rather, it is to serve the Grail – that is, to live a life not of ego but of our most authentic nature, our souls. As Robert A. Johnson so eloquently sums it up,

One can not pursue happiness; if he does he obscures it. If he will proceed with the human task of life, the relocation of the center of gravity of the personality to something greater outside itself, happiness will be the outcome.”

For a beautiful examination of this myth in much greater detail, please see the book “He: Understanding Masculine Psychology” by Robert A. Johnson, from which all quotes above were derived.

Who is Dr. Corvalan?

Through the many journeys of his life, from his formative years, through his lifelong career as a doctor and healer, to his sweeping search for meaning and transcendence in life, Dr. Jaime G. Corvalan, MD, has energized innumerable individuals to live healthy, meaningful lives. Ask the doctor where he’s from and he’s happy to tell you, “I’m a citizen of the Earth.” The doctor sees all people as one, and feels that we are all on a journey of discovering meaning and a higher purpose in life; in fact, we’re here to take the greatest journey of all, the journey of our true selves, our souls.

Through the many journeys of his life, from his formative years, through his lifelong career as a doctor and healer, to his sweeping search for meaning and transcendence in life, Dr. Jaime G. Corvalan, MD, has energized innumerable individuals to live healthy, meaningful lives. Ask the doctor where he’s from and he’s happy to tell you, “I’m a citizen of the Earth.” The doctor sees all people as one, and feels that we are all on a journey of discovering meaning and a higher purpose in life; in fact, we’re here to take the greatest journey of all, the journey of our true selves, our souls.

Dr. Corvalan’s work reflects a life both steeped in the world of intellect (as an extremely well-known Urologic Surgeon, former UCLA Clinical Professor of Surgery, and alumnus of the Cleveland Clinic) and in the world of metaphors and language of the soul (through his extensive interests in Jungian psychology, symbolism, mythology, history, art, and classic literature).

I have been truly blessed in my life, and, as I enter the second half of my life, it is important to me that I share those blessings with others,” says the doctor. “I’ve come to realize that the most vital thing for us to understand is the importance of consciousness – everything is consciousness.

When we consider the entirety of human history – and, indeed, of the unfolding of the universe – the evolution of our awareness, of our recognition of consciousness, is at the heart of all that we’ve experienced, good and bad. My abiding hope and intention is to help to grow consciousness, in myself and within everyone, so that we can move to a place where we all operate from our hearts, from our most authentic selves – our souls.”

Your Own Hero’s Quest

You may wish to ask yourself some important, penetrating questions when embarking upon your own Hero’s Quest: By What Truth Do I Live? Who’s Life am I Living? Who am I Being? To create your own life, to reconnect with the divine, you must break free of the constraints of your ego life by overcoming your fear and aligning your ego with your soul.

The skills, knowledge and power you acquire in the first part of your life must be brought to serve your soul, not your ego. In service of the ego, power can be abusive, tyrannical, and will destroy you. What is required is what the great philosopher, Arthur Schopenhauer, called the highest form of human morality, compassion.

Dr. Viktor Frankl, neurologist, psychiatrist and Holocaust survivor, found that even in the most horrific conditions of Nazi labor camps, one could find meaning in life, that the human spirit is indomitable. We must accept that suffering is a part of our quest, and that it is required for us to grow and free our souls. “Suffering” has roots in the term “sacred,” and is an inevitable part of our Road of Trials . . . and with Compassion, we can share in and empathize with the suffering, the sacred experience, of everyone and everything.

Look deeper, let go of arrogance. What is Your Mission? What is Your Bliss? What is Your Calling? Like Parsifal, Siegfried, even Luke Skywalker, we must let go of hubris, arrogance, foolish pride. Your Soul, Your Joy, Your Adventure Awaits!