– By Dr. Jaime G. Corvalan, MD, FACS

We are increasingly inundated in Western culture with corporate and profit-driven forms of entertainment, a seemingly never-ending cacophony of hollow or trite productions who’s underlying objective is driving the company bottom line. All of this highly produced, artificial noise, however, lies upon a foundation of something we all have in common as a species: story-telling.

We are story-tellers and have been since perhaps even before the advent of written language. But why? Stories, especially those of a mythic nature, speak to us at a deeper level than even the intellect. They connect with us at an archetypal level, allowing us to experience emotions, feelings and ideas that are not merely common to all humanity, but to our transcendent consciousness – what some would call the soul.

As such, mythologies and stories need not be literally true for them to have power and significance for us. Whatever the archeological record that may exist for Jesus, what matters is the story. Jesus’ story embodies and puts into focus the need to live out of empathy, love and compassion; his story underscores the need to live in a consciousness of the heart and soul, eschewing the desire for power, control and domination. The story has power!

Before literacy became more commonplace, the character and identity of a culture, people and society was often passed down through spoken stories and myths. Myths nourish not just the mind but are the language of our very souls, and for this reason – among so many others – we need them!

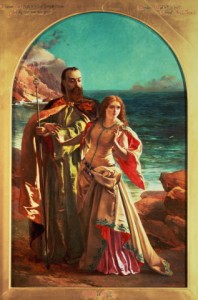

The wonderful author Helen Luke used her encyclopedic knowledge of great literature and Jungian psychology to share some of the collective wisdom of human story-telling. In her analysis of Shakespeare’s “The Tempest,” in her book “Old Age: Journey into Simplicity,” she shows in a powerful way how Prospero’s devotion to something beyond himself – his daughter Miranda – is what would save him. By sharing the genius of Shakespeare, she was able to demonstrate this kernel of wisdom not in dry, academic terminology but in the rich, soulful words of perhaps the greatest story-teller in Western history.

We need stories like this! We could talk about the dangers of hubris, arrogance and pride in a formal debate setting, or we could watch as Odysseus, the “sacker of cities” and the great, conquering hero of Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey, loses the lives of his crew as he arrogantly and carelessly blinds and taunts the giant Cyclops Polyphemous. Because of his massively inflated ego, his crew dies and he spends 10 years trying to return home. Through the telling of this story, we can feel what he felt, we come to understand at an intuitive level the dangers of acting out of excessive pride and deception.

Or consider the meaning of honor and loyalty. How? We can again debate their meanings, or we can share the story of Achilles and the Trojan War, again in Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey. To the ancient Greeks, glory was one of the greatest rewards for valor and loyalty, especially in battle; none knew this better, perhaps, than the greatest of all Greek warriors, Achilles. When, however, his king, Agamemnon, summoned him to fight in the Trojan War, Achilles refused. The king sends his emissary, Odysseus, to persuade him, promising him riches and the chance to die a hero in the glory of battle.

Achilles again refuses, for the king had dishonored and enraged him by taking from him his beloved Briseis. Achilles’ refusal to fight for a dishonorable king demonstrates that true honor is something far greater than glory; it underscores the need to understand the distinction between honor and reputation. Achilles does eventually return to the battle – completely changing the fortunes for the Greeks – only, however, out of loyalty and to avenge the death of his friend, Patroclus.

Great stories like those found in the great mythologies of humanity, from the Iliad and Odyssey to the Bible to the Mahabharata and Bhagavad Gita, and to countless others, speak to our souls.